Balancing Resiliency and Efficiency

Supply chain executives face a new optimization problem: becoming more resilient while minimizing costs. Here’s how to strike the right balance.

TAKEAWAYS:

● Disruptions over the past few years have exposed vulnerabilities in manufacturers’ existing supply chains.

● As a result, conventional approaches may no longer be enough to achieve the desired level of supply chain assurance.

● This article highlights a range of new approaches and tools manufacturers are deploying as disruption becomes the norm.

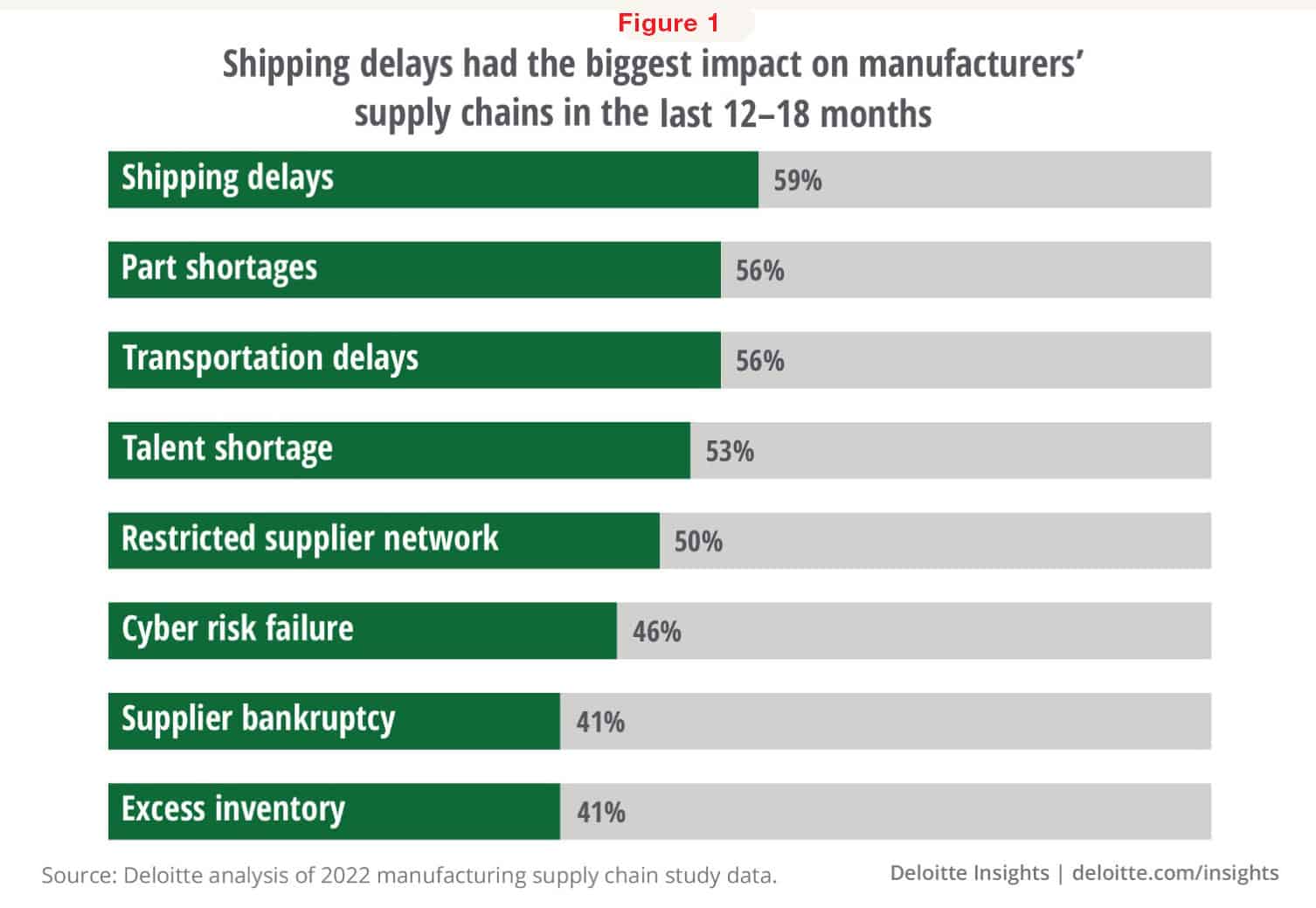

Shipping delays, parts shortages, and transportation delays due to truck driver shortages and congested ports had the greatest impact on manufacturing companies in the past 12–18 months, according to survey respondents (figure 1). Production and profits are the two key areas where this impact has been felt, and a majority of respondents report a negative impact to profits of up to 13%.

These factors suggest that supply chain executives are working to solve a new optimization problem with more stringent constraints: Costs still need to be minimized, yet resilience and redundancy should be built in to assure supply. This calculation is ever more challenging given the rising costs of energy and materials and labor, current workforce shortages, and ongoing logistics challenges resulting from two years of pandemic disruptions.1

The exigencies of the current environment are bringing a new focus on time-tested skill sets. Several supply chain executives surveyed emphasized that in volatile environments, the familiar skill of supplier relationship management can become even more important to avoid disruption. However, junior employees may need to be taught these skills as most are used to working in a demand-driven environment. The sudden shift to a supply-constrained business model meant not all employees were armed with the needed relationship management skills to work closely with suppliers as partners to manage forecasts, lead times, inventory strategies, and costs.

In many cases, this partnership has developed as quarterly supplier reviews turned into daily calls between senior supply chain executives and the CEOs or CFOs of their suppliers, sharing information and helping each other navigate the business environment (figure 2). For example, one company worked through its supplier as a partner to find an alternate source of chips during the chip shortage, thereby achieving greater flexibility and visibility. Another company worked closely with suppliers as shipping options from Asia were reduced and freight was moved to air cargo, which incurred higher costs.2

Proactively Managing Multiple Tiers

Supply chain executives have been drawn into management not just of their primary suppliers, but increasingly of secondary and tertiary suppliers as well. Several executives interviewed noted that previously they did not get involved beyond Tier 1, but the dynamics of the current environment drove a need to increase visibility. For example, if Tier 3 suppliers were unable to give firm dates for shipping, often this potential weak point wasn’t visible to primary suppliers or to the company itself, and potential delays were not flagged early enough. To address this risk, one company interviewed has begun working closely with its own suppliers to apply transparent decision-making based on metrics and benchmarking to that supplier’s suppliers. This can provide the company more visibility and clarity in terms of the companies with whom its suppliers are contracting.

The semiconductor shortage, which has affected industries from automotive to handheld electronics, raises the question of how to achieve resilience when the market is highly concentrated. In the semiconductor supply chain, some suppliers are unique—for example, worldwide, there’s only one epoxy supplier and two suppliers of cutting-edge chips.3 Moreover, the global semiconductor industry has been running at over 95% utilization since December 2020, which is well over the 80% utilization rate normally considered full capacity, suggesting additional production capacity is needed.4

“Supply chain executives have been drawn into management not just of their primary suppliers, but also secondary and tertiary suppliers.”

The passage of the CHIPS Act in 2022 has helped jump start investment in additional production capacity in the United States. For example, a semiconductor manufacturer is considering building four semiconductor chip fabrication plants (fabs) at a cost totaling nearly US$30 billion. Intel announced plans for an initial investment of more than US$20 billion to construct two new fabs in Ohio, a new region for chip-making.5 And it isn’t just US-based companies considering adding capacity in the country: South Korea’s Samsung has proposed a US$17 billion fab in Taylor, Texas, and has also recently submitted an application with the Texas comptroller outlining a long-term plan to build up to 11 chip-making plants in Texas, an investment that would be worth more than US$192 billion in the coming decade. Arizona is also poised to receive investment for chip manufacturing.

Supplier Risk Considerations

As supply chains elongate and supply bases increase with new sources created, procurement teams are becoming more central to enterprise risk management. Procurement and supplier risk management functions should work more closely with suppliers and their compliance and risk management departments. Executives interviewed for the study are engaging more often and earlier with third-party risk management protocols. The historic approach of a point-in-time assessment, even if done annually, may no longer be sufficient for organizational risk management objectives. Companies must sense, monitor, and be ready to take action as needed.

Sensing: Leading companies are beginning to use intelligent sensing of data, including social media, in combination with assessments and investigations, to enhance the effectiveness of their suppliers in managing third-party risk.

Monitoring: As companies identify their critical risk domains, from financial health to geopolitics to cybersecurity, they can develop technology-enabled processes to proactively monitor their third-party ecosystem and identify the early warning signs that could trigger action.

Taking action: For quick action, such as switching to a new supplier, having a preapproved response plan can be critical. One company requested all its vendors participate in response planning, outlining COVID-19 contingencies, such as if parts weren’t received and trucks stopped delivering. Similarly, additional suppliers need to be “prequalified,” such that the contracting work could be done already, shortening lead times.

Scenario planning: Management teams can also identify potential scenarios in advance, along with sub criteria that help indicate the best response plan in a given situation. Executives should decide in advance who has decision-making power in each scenario and how to, for example, reduce downtime and address breach of contract incidents.

Moving Away from JIT Approaches

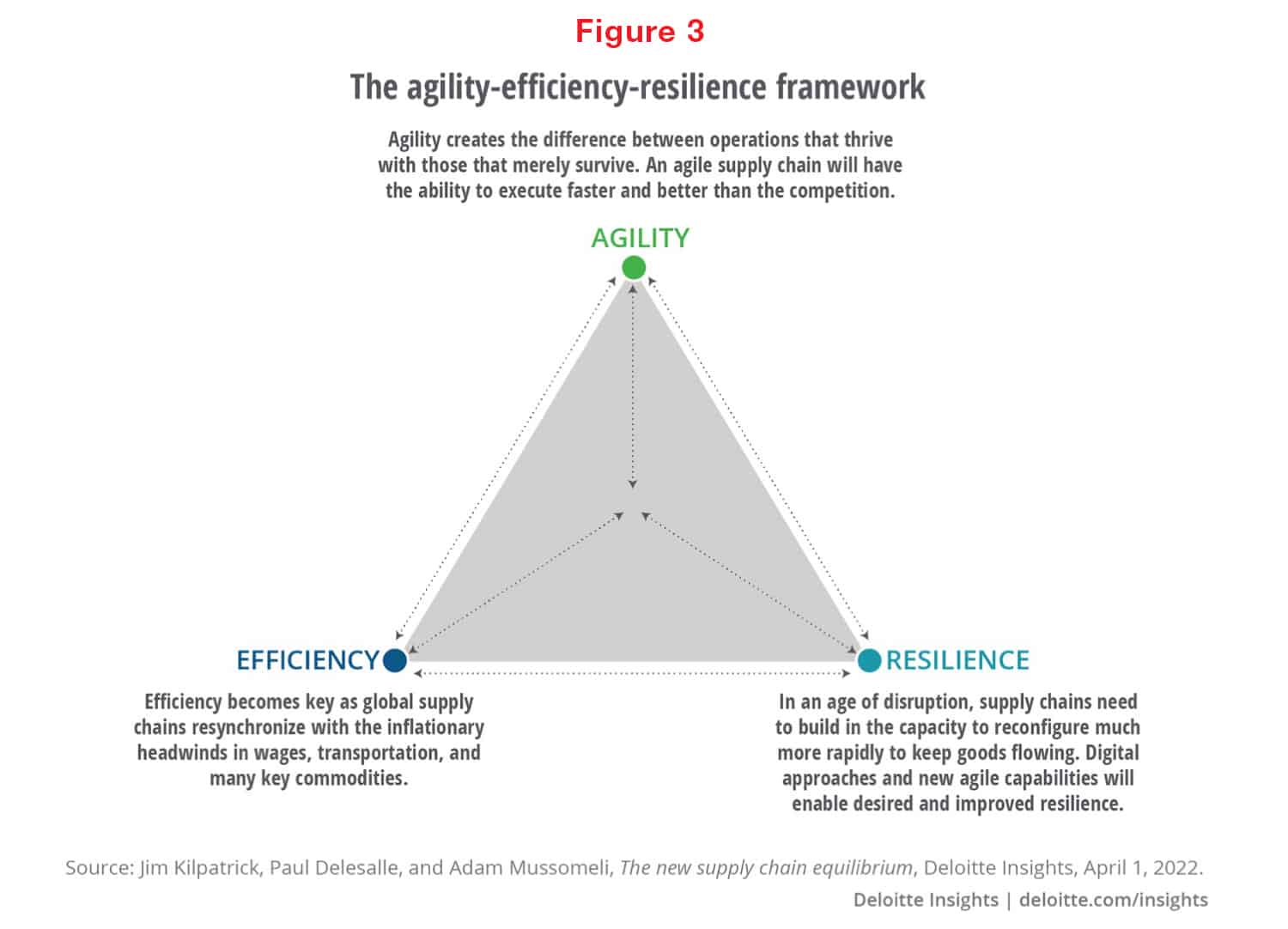

Manufacturers seem to be drifting away—maybe only temporarily—from just-in-time approaches to help manage the constraints of higher labor and materials costs, logistics bottlenecks, and labor shortages. One executive explained that in early 2021 his team decided they needed to move away from the focus on cost and orient increasingly on business continuity and customer satisfaction. Executives draw a distinction between operational challenges, which can be solved through improved supplier relationships and visibility, and logistics and external challenges, which are out of the supplier’s or company’s control. However, to manage external challenges, supply chain leaders need to be well-equipped and strike the right balance between agility, resilience, and efficiency (figure 3).6

Building out agile processes: agility and flexibility are potential game changers. Flexibility of design could be used to standardize product-specific parts, allowing a standardized part to be used across products that would require minimal customization. For example, Tesla uses a number of chips in its vehicles for various control and infotainment systems, and its self-driving software. During the ongoing semiconductor shortage, Tesla swiftly changed to new microcontrollers, while simultaneously developing firmware for new chips produced by new suppliers.7

Mitigating transportation challenges: the persistent labor shortage in manufacturing, which has been exacerbated by the pandemic, has contributed to port delays, slower warehouse processing, and a truck driver shortage. As one executive explained, no matter how reliable your supplier, a labor shortage at a port can still cause a shipping delay. To address this disruption, building redundancy or resilience is needed. One company shared that it is looking at diversifying supply routes on the West Coast, possibly adding a Canadian port.

Developing resiliency: to build resiliency, in some cases manufacturers are actively partnering with other manufacturers or are investing in their suppliers to support building more production capacity. Executives interviewed described a continuum of collaboration ranging from buying capacity in advance from suppliers to actually taking equity stakes in certain critical suppliers. There have been several examples in which industrial manufacturers are expanding their activities into adjacent areas. Our study highlights that Tier 1/Tier 2 suppliers are likely to coinvest or partner with other Tier 1/Tier 2 suppliers in emerging technologies to develop new capabilities and advance through logistics and transportation challenges.

“Manufacturers seem to be drifting away – maybe only temporarily – from Just-in-Time supply chain approaches.”

In one example, an industrial technology company made an acquisition to expand its presence through existing distribution channels, and also to expand in the aftermarket filtration space. In other cases, investment is focused on fostering more competition in a given market, ultimately to build more choice among existing producers. These additional investments could clearly have an impact on the industry’s cost structure, but that reduction in margin could be worth the resilience ultimately provided through developing a deeper market with more producers.

Getting to Resiliency

As manufacturing executives solve the current supply chain optimization problem, they are leveraging familiar mitigation strategies to balance resilience with efficiency. But they are also wielding new skill sets and tools to manage the tougher constraints of rising costs, labor shortages, and logistics bottlenecks to achieve agility.

Here are three sets of recommendation to boost resiliency:

Strengthen existing supplier relationships to increase resilience:

● Work closely with suppliers to help them apply metrics to their Tier 2, 3, 4 suppliers

● Agree on mutually beneficial KPIs so that all parties know what to expect from one another

● Help suppliers maintain data on their suppliers’ throughput to boost transparency and assurance

● Train newer employees on relationship management

Engage with multiple suppliers to balance efficiency and resilience:

● Correctly calculate the benefits of engaging multiple suppliers with the costs of lower margins and reduced control

● Use dual sourcing to achieve some cost control where possible, evaluating investing in development of additional suppliers in a niche market

● Have scenarios in place and alternative suppliers preapproved, conducting practice drills to make contingency plans more effective

● Locate additional production or alternate suppliers close to markets to reduce transportation costs and exposure to shipping delays

Employ digital solutions to boost efficiency and resilience:

● Implement warehouse automation in response to workforce shortages

● Move to digital solutions that increase visibility beyond Tier 2 suppliers

● Boost collaboration by initiating high-level information-sharing between all parties with the help of easy to-use technologies

● Track potential sources of logistical disruption such as restricted routes and workforce shortages

Manufacturing executives are acutely aware of causes for both internal and external disruption and are taking steps to build redundancy into supply chains to assure business continuity. Though these efforts may lower margins, they can increase agility, reflecting the new balance that manufacturers are achieving between efficiency and resilience. N

Endnotes

1. Stanley Porter and Kate Hardin, “Energy and commodities outlook: Disruptions from the Russian invasion of Ukraine,” Wall Street Journal, June 3, 2022.

2. Insights gleaned from manufacturing executives’ interviews conducted in July 2022.

3. Deloitte, Anchor of global semiconductor: Asia Pacific takes off, 2021, p. 9.

4. Semiconductor Industry Association, Increasing chip production: Industry shouldering in to addressing shortages, 2022, p. 1.

5. Intel Corporation, “Intel announces initial investment of over €33 billion for R&D and manufacturing in EU,” news release, March 15, 2022.

6. Jim Kilpatrick, Paul Delesalle, and Adam Mussomeli, The new supply chain equilibrium, Deloitte Insights, April 1, 2022.

7. Lambert, “How Tesla pivoted to avoid the global chip shortage that could last years,” Electrek, May 3, 2021.

About the authors:

Paul Wellener is a Principal within the US Industrial Products & Construction practice with Deloitte Consulting LLP. He has more than three decades of experience in the industrial products and automotive sectors and has focused on helping organizations address major transformations.

Stephen Laaper is a principal at Deloitte Consulting LLP and a manufacturing strategy and smart operations leader in Deloitte’s Supply Chain & Network Operations practice. He helped build Deloitte’s Digital Supply Networks (DSN) methodology that uses existing and “next gen” technologies to drive efficiencies in operations and across the supply chain.

Kate Hardin, executive director of Deloitte’s Research Center for Energy and Industrials, has worked in the energy industry for 25 years. She leads Deloitte’s research team covering the implications of the energy transition for the industrial, oil, gas, and power sectors.

Aaron Parrott is a managing director with Deloitte Consulting LLP. With more than 20 years of experience in supply chain and network operations, Parrott’s focus is helping clients complete large- scale transformation in the supply network, developing analytic solutions to address difficult business issues, and implementing digital solutions to manage complex supply networks.

This article contains general information only, does not constitute professional advice or services, and should not be used as a basis for any decision or action that may affect your business. The authors shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person who relies on this article.